John Steinbeck, the U.S. Nobel Prize-winning author, was known for his gritty realism, sympathy for the marginalized and downtrodden, understanding of human nature, and romanticization of the countryside. These are all themes explored by certain musicians. While the scope and medium of a novelist differ greatly from those of a musician, and such comparisons are necessarily limited, striking parallels can be drawn between Steinbeck and some modern troubadours.

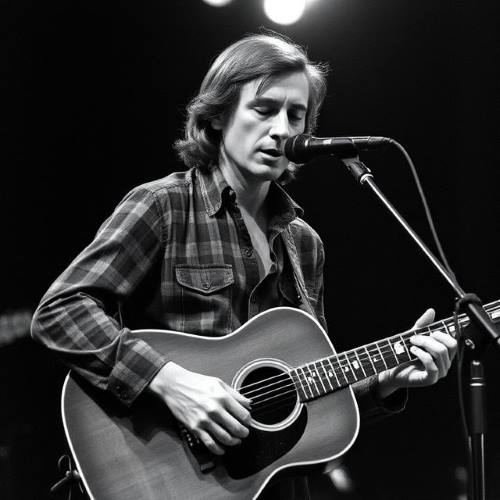

So, who is the John Steinbeck of music? In short, it’s Townes Van Zandt, a relatively little-known country singer who lived a life as desperate and troubled as any character in a Steinbeck novel.

Townes Van Zandt was born on March 7, 1944, in Fort Worth, Texas, into a wealthy family. Despite his privileged upbringing, he was drawn to the edges of life, chasing poetry and music instead of money. He struggled with mental health from an early age and underwent electroshock therapy in his twenties, a trauma that haunted him for the rest of his life.

In the 1960s and ’70s, he emerged as one of America’s most gifted and tragic songwriters. His songs—like “Pancho and Lefty,” “If I Needed You,” and “Waiting Around to Die”—were stark, haunting, and deeply human. Though never a commercial success, he was revered by peers like Willie Nelson, Emmylou Harris, and Steve Earle, who once said, “the best songwriter in the world, and I’ll stand on Bob Dylan’s coffee table in my cowboy boots and say that.”

Townes lived hard, drank heavier, and died too young—on January 1, 1997, at the age of 52.

Like Steinbeck, his songs told the stories of the troubled and the marginalized. There is a brevity and economy to his writing that cuts to the bone—demanding honest understanding but never pleading for sympathy. He often told tales of well-meaning people falling into hardship, or deeply flawed individuals who remain painfully relatable. His songs frequently feature female protagonists, such as in “Tecumseh Valley” and “St. John the Gambler.”

His music is rooted in the American Midwest, often lingering in a mythical rural America of reclusive cowboys and outlaws. Like Steinbeck, Townes’s lyrics evoke a love for the land—its beauty, its sustenance, and the identity it imparts. Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath explores the devastating impact of the Joad family’s forced uprooting, where the beauty of the land stands in contrast to the brutality of life. Townes’s music is perhaps even more melancholic. For him, the land feels like a place of solitary exile, offering faint hope of freedom or cleansing rather than a source of renewal. Still, there is no denying the romanticization of the countryside in songs like “Our Mother the Mountain,” “Flying Shoes,” and “Tecumseh Valley.” “Lungs” laments the destruction of nature and environmental collapse in parallel to his own health issues.

Townes’s most famous song is “Pancho and Lefty,” made famous by Willie Nelson’s cover. A subtler piece of storytelling in song would be hard to find. It recounts the unlikely friendship between Lefty, a singer, and Pancho, a bandit—ending in betrayal. Lefty gives Pancho up, seemingly for reward, leading to Pancho’s death. But Lefty is condemned to a life of shame: “Lefty, he can't sing the blues / All night long like he used to / The dust that Pancho bit down south / Ended up in Lefty's mouth.”

The repeated chorus, “All the Federales say they could've had him any day / They only let him slip away out of kindness, I suppose,” echoes Lefty’s effort to justify his betrayal. It’s a subtle, internal negotiation, trying to convince himself that Pancho would’ve died anyway regardless of the betrayel. The final chorus—“A few great Federales say / They could have had him any day / They only let him go so wrong / Out of kindness, I suppose”—deepens the ambiguity. After many years, the ache for absolution lingers, even as memory fades.

Often referred to as the "Dust Bowl Balladeer," Woody Guthrie’s songs like “This Land Is Your Land” echo themes in Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath. Both highlighted the struggles of the working class during the Great Depression and offered poignant social commentary.

Known for his narratives about the American working class, Bruce Springsteen drew direct inspiration from Steinbeck. His album The Ghost of Tom Joad references a central character from The Grapes of Wrath, exploring themes of economic hardship and social injustice.

Mellencamp’s music often portrays small-town life and reflects themes found in Steinbeck’s novels. His co-founding of Farm Aid and advocacy for family farmers earned him the 2012 John Steinbeck Award.

John Prine’s lyrics paint vivid portraits of ordinary life—tackling love, aging, loss, and social issues with humor and grace. Many view him as a musical heir to Steinbeck for his deep empathy and storytelling.

Through his project Ray’s Vast Basement, Bernson created "musical fiction" that wove together narrative and song. He even developed a song cycle for a stage adaptation of Of Mice and Men, directly connecting his work to Steinbeck’s legacy.

While no single musician can embody all of Steinbeck’s literary depth, these artists echo his concerns—poverty, dignity, resilience, and the American landscape. Yet it is Townes Van Zandt whose lyricism, sorrow, and piercing human insight most closely mirror Steinbeck’s moral clarity and emotional range. His songs are intimate portraits of life's quiet devastations, as timeless and aching as anything Steinbeck ever wrote.